I’ve recently finished writing a book about creating high performance animations and interactions with Ionic, which I put together over the course of around 3 months and ended up producing a chunky tome weighing in at about 500 pages. You can find out more about the book below:

Check out the book: Advanced Animations & Interactions with Ionic

Going into writing this book I felt that I had a good understanding of the issues facing web animations in general and how to implement them successfully in an Ionic application, but one of the great benefits of writing an in-depth book like this is that you tend to solidify and expand your knowledge of the topic a great deal. The purpose of this article is to highlight some key lessons about animations and performance that stood out to me by the time I finished writing that last page.

There are definitely animations and interactions out there that can’t be executed as smoothly within a web view as they could outside of the web view in a native application. I didn’t want to shy away from challenging scenarios for this book, so when finding examples to implement I picked a bunch of common and interesting scenarios without any regard to how feasible it would be to implement them with high performance using Ionic Animations and Gestures. Somewhat to my surprise, there wasn’t a single example I attempted that I ended up having to scrap from the book due to just not being achievable with smooth performance.

I’m sure these examples could be found, there is definitely a distinction between what can be done on the web and natively with animations. My point is that most likely the majority of animations and interactions that you would want to add to your applications can be done with a high level of performance in an Ionic application. As long as you have a decent understanding of how the browser renders frames to the screen, and how the animations/interactions you are creating interact with that process.

This article won’t be a rundown of general performance concepts, it will focus on things that I either learned whilst writing this book or things that became clearer for me through writing this book (e.g. that the limitations web views impose on animations aren’t actually all that limiting). Of course, I would recommend my new book to those Ionic developers of you wanting to gain a clearer understanding of performance and animations, but the key performance concepts to understand above all else are:

- Understanding the browser rendering process

- Achieving an average frame rate of around

60fps - Keeping response times for interactions under

80-100ms - Only animating

transformandopacity(with rare exceptions for other properties)

1. You can do a lot with just transforms and opacity

It might seem extremely limiting at first to have a rule like “only animate transform and opacity”. When I set out to write this book I already had the opinion that there is a surprising amount you can do with just these two properties, but even still I expected to have to make some exceptions here and there. However, just about every single example in the book is achieved primarily with the transform property, this includes:

- Sliding Drawers

- Expanding/Shrinking Cards

- “Star Wipe” style screen transitions

- Draggable chat bubbles

- Animated progress bars

- Sliding action items

- Tinder style swipeable cards

- “Morphing” elements from one size/position to another

- Parallax style shrinking/fading effects

- Shrinking delete animations

Even an example where it seemed like there was no other way to achieve the animation without animating height was achieved through a transform (we will talk about that later).

2. The will-change CSS Property is Powerful

Going into writing this book, I didn’t yet have a full appreciation or understanding of the will-change property. It was something that had come up for me before, but I mostly considered it to be a kind of niche optimisation that has rare use cases and probably wouldn’t make all that much difference.

It wasn’t until I read Everything You Need to Know About the CSS will-change Property by Sara Soueidan that I gained a full appreciation for the will-change property and all of its potential (for both good and harm).

I won’t rehash here what is better explained in that article, but in general, the will-change property allows us to hint to the browser what we will be changing (e.g. a transform or opacity) such that the browser can then make the appropriate performance optimisations in advance (before our animation/gesture begins). This can lead to huge performance gains, but it is important not to overuse it, as telling the browser to optimise the wrong things at the wrong time can lead to performance consequences. The general approach I used in the book was to not use it at all, unless I could see that the performance of one of my animations/interactions was suffering in a way that might benefit from will-change. I would then implement will-change and measure the performance impact that it had (only keeping the change if it leads to performance improvements).

Quite a few of the examples in the book have had rather drastic performance improvements by utilising will-change. In some cases, this was the difference between sub-par performance and a consistent 60fps.

To give you an example, one of the components from the book involves sliding an <ion-item> to the right with a gesture (similar to Ionic’s <ion-item-sliding> component). Even though this gesture was achieved by animating a transform it was still causing constant paints throughout the gesture (we will talk more about paints in just a moment). The performance was still decent, but I was able to achieve a significant performance boost by utilising the will-change property.

How you use the will-change property is also important. Generally, it should only be added when you are about to use it and removed afterward. In this example, I utilised the onWillStart handler that is available through Ionic Gestures to dynamically add the will-change property to the specific element being dragged:

onWillStart: async () => {

style.willChange = "transform";

},and then removed it in the gestures onEnd handler:

onEnd: () => {

style.willChange = "unset";

},In this way, the browser is only optimising the element that is currently being interacted with when it needs it, not every single element on the screen that this gesture is attached to. If you have 50 of these sliding items on the screen, most you will never even touch, so performance optimisations on these would be a waste of browser resources.

On the other hand, for elements that will be constantly interacted with it is justifiable to add the will-change property directly to its CSS styles. I took this approach for the “sliding drawer” example in the book since it would likely be constantly opened and closed:

:host {

will-change: transform;

}3. The Power of Paint Flashing

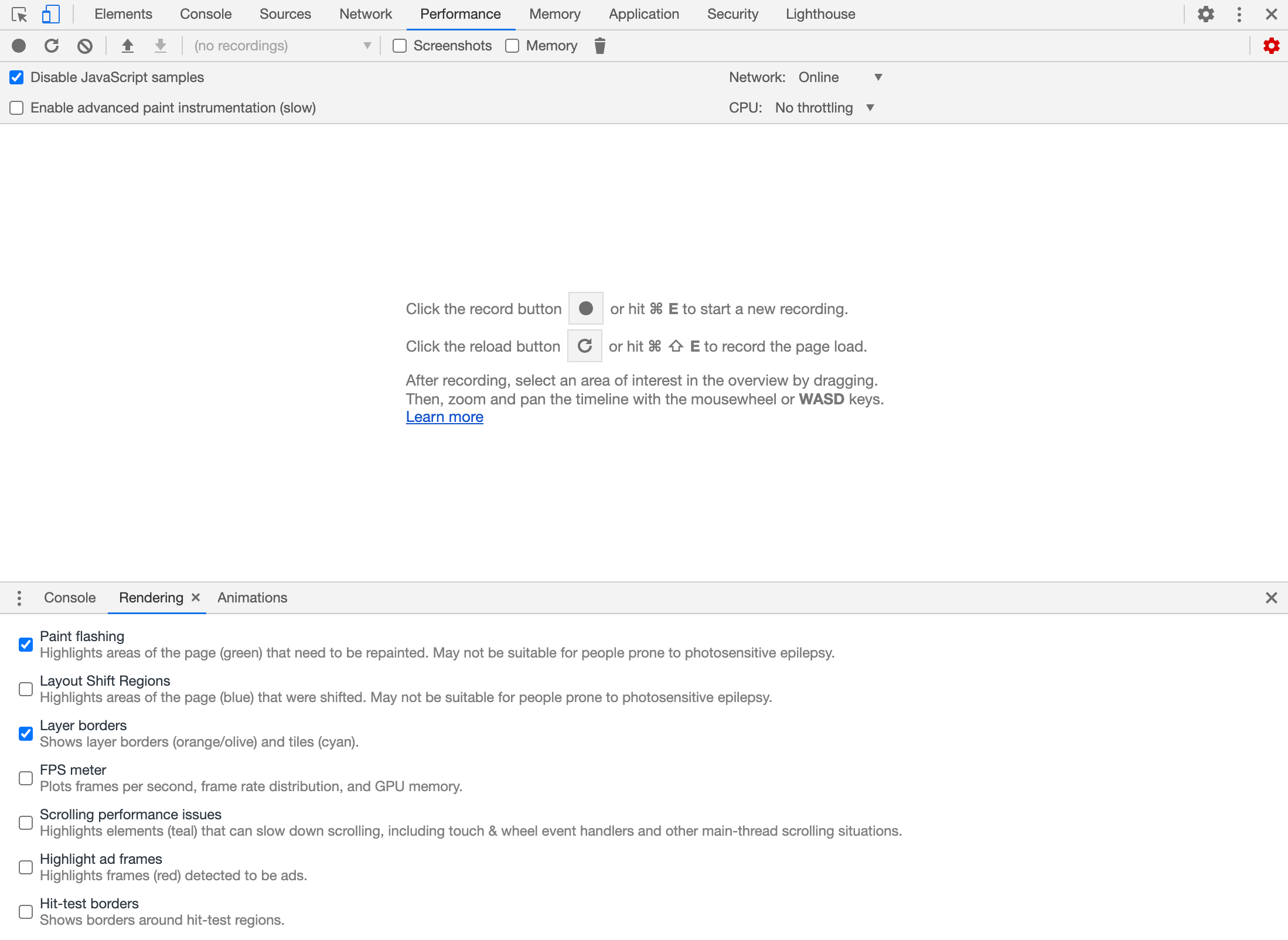

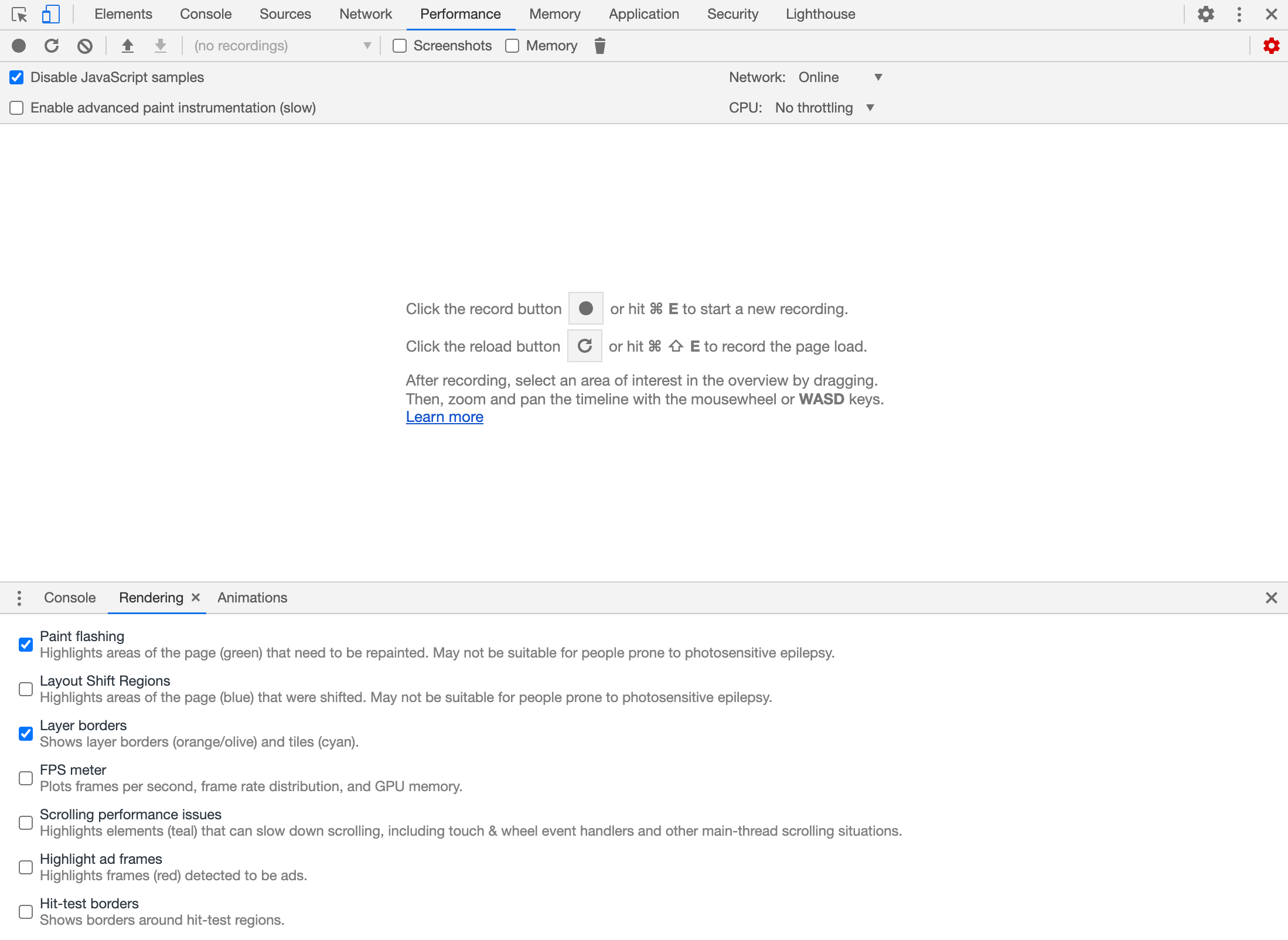

I did a lot of animation optimisation throughout writing this book, so I was able to really hone in on what specifically in the performance/animation debugging toolkit was most useful. The Paint Flashing option that you can find in the Rendering drawer in Chrome DevTools was something that I seldom used, but now I have it enabled pretty much every time I am trying to optimise something:

What this option will do is flash a green box over areas of the screen that are triggering the “paint” step of the browser rendering process (i.e. new pixels are being rendered to the screen). If you can see a lot of paints being triggered throughout your animation/interaction it might be cause for concern - although a “paint” usually isn’t as concerning as triggering a “layout” in the browser rendering process, it can still have a significant impact on performance.

Sometimes paints are unavoidable, but sometimes its a telltale sign that an element that should be on its own layer and being, is not on its own layer. When rendering your application the browser will promote some areas onto their own layer that is “composited” into the rest of the application - this allows the layer to move around freely and be transformed without needing to repaint it all the time. However, the browser won’t always optimise your applications rendering perfectly, and being able to see where this is happening is immensely powerful. If we can spot things that aren’t on their own layer that we think should be, we can usually change that by using a transform or the will-change property.

The example above is from one of the examples in the book before it was optimised. As you can see, as the gesture begins/ends it is triggering paint flashes. To optimise this, I was able to use the will-change property which completely eliminated these paints.

The Layer Borders option also helps with this, since elements that are on their own layer will be outlined, but I find this less obvious and don’t use it as much.

4. Testing with 6x CPU Slowdown

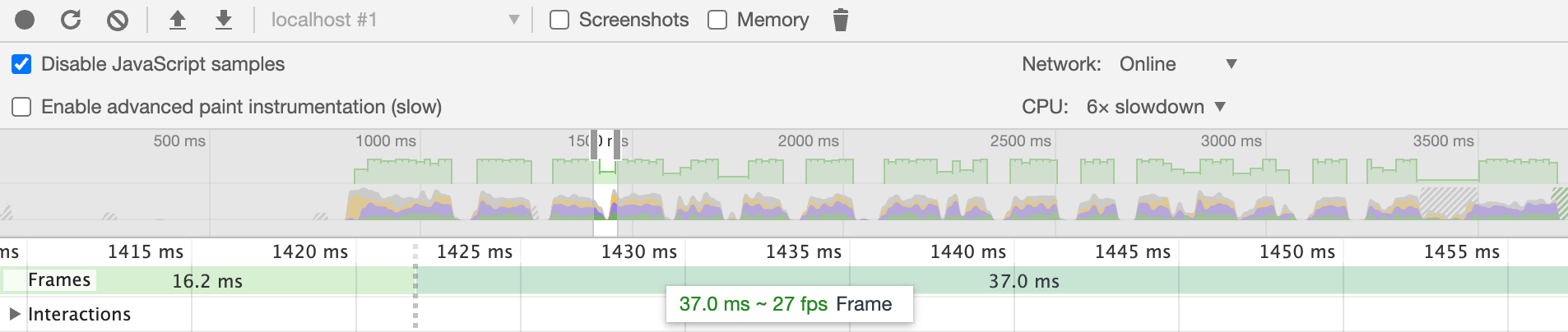

This is another one of those features of Chrome DevTools that I never really utilised, but that proved to be immensely useful. When creating a performance snapshop in Chrome DevTools, if you click the little cog icon in the top-right, you will be given some extra settings which include the ability to throttle the CPU performance.

The CPU is primarily what is responsible for doing the work required to render frames to the screen, so if we intentionally slow that down it can highlight potential problem areas in our animations/interactions more clearly. On a powerful machine, even some poorly designed animations can be executed well, but if we set the throttling option to 6x CPU Slowdown potential performance problems become more apparent:

I utilised this option for optimising every single example in the book.

5. The difference between jank and 60fps can be tiny

There are a lot of different ways you can go about implementing the same animations. There are the performance improvements that will quickly become obvious like using translateX(10px) to move an element 10px to the right instead of using margin-left: 10px (the former might only trigger the “composite” step in the browser rendering process, whereas the latter would also trigger “layouts” and “paints”). Then there are the more subtle and less obvious performance improvements like adding will-change: transform.

As we have touched on in this article, even with using good practices like only using transforms there can still be jank. Sometimes the kind where you can’t really see it but you can feel it, and that has a lot to do with not quite hitting a consistent enough 60fps. Really pushing for those little extra optimisations and paying attention to details by measuring performance can be the difference between an animation/interaction that just feels a little off, and one that feels smooth and satisfying.

6. Performance optimisations can get very creative

Sometimes squeezing out those last bits of performance can mean tiny details like will-change, sometimes it can mean taking a completely different approach to how your component works - perhaps even in ways that make it way more complex.

As you get more comfortable with performance concepts, specifically with the way the browser renders frames to the screen, you can start getting a lot more creative with your solutions and perhaps even achieve 60fps on animations/interactions that didn’t even seem at all possible. If you really understand what the browser is doing, it becomes a lot easier to see how to work with the browser rather than just telling it what to do.

There is a great example of this in the book where we optimise an animation that shrinks an item away when it is deleted by using height (which is bad for performance), and instead we use a transform instead to achieve the same effect. This sounds way simpler than it actually is, because there are reasons why using a transform in this circumstance is problematic. I created a summary of the approach for this in the video below:

These sorts of solutions can be very situation dependent, so the optimisation approach will differ vastly depending on what exactly you are trying to achieve. This is why I see this as kind of the “endgame” for animation/interaction optimisation on the web, it’s where you can really put your skills to the test. These are non-obvious optimisations that can make an otherwise seemingly undoable animation doable.

Summary

There were plenty more things I learned throughout writing this book, but these are the things that stood out to me the most related to performance. There is of course plenty more for you to learn as well if you are interested in check out out the book.